Reclaiming the Future – The Unfinished Revolution of Nigeria’s Youth

A synoptic analysis and lessons from the Lecture delivered by Comrade Baba Aye at the Social Action Camp 2025

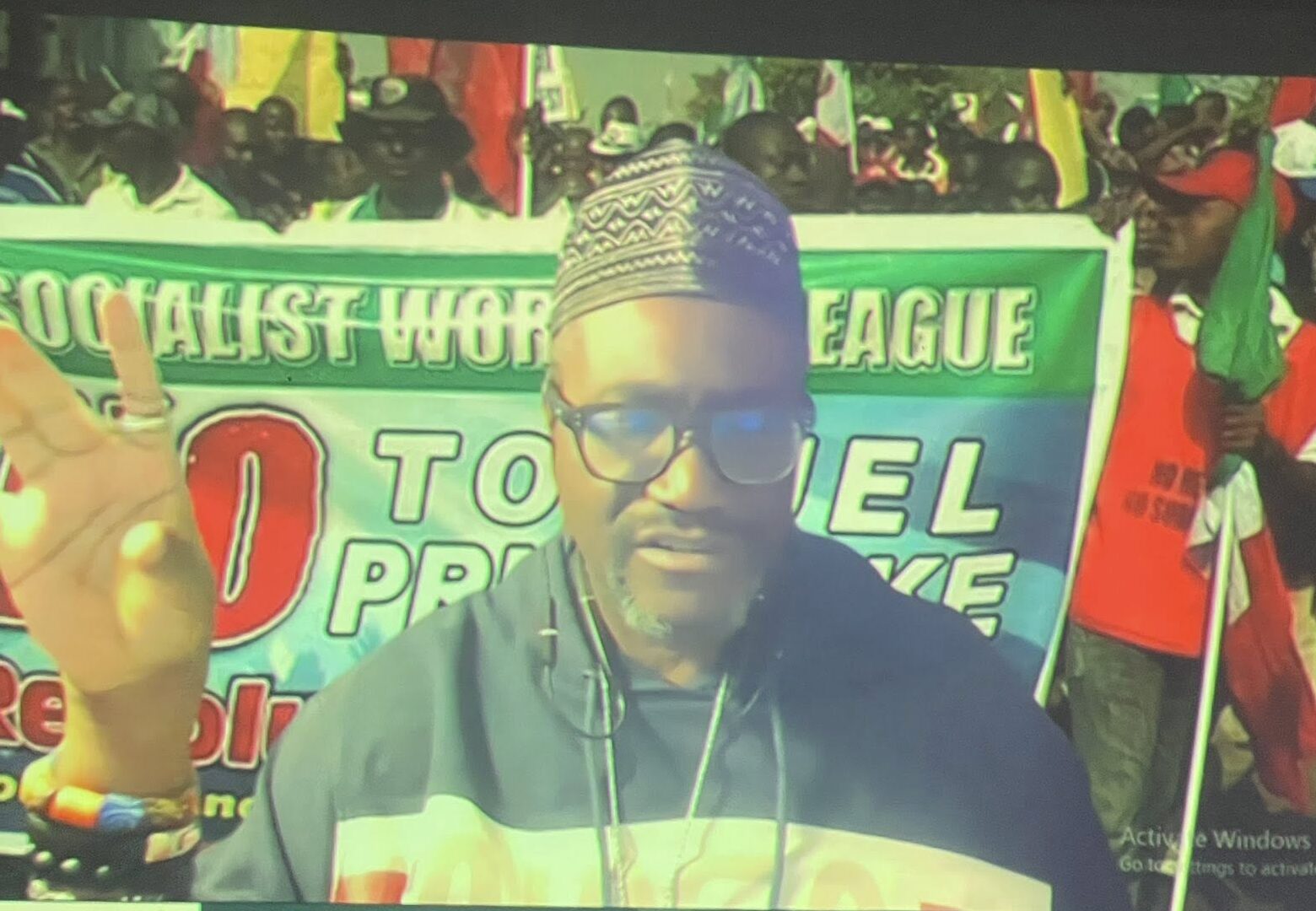

The air at the Social Action Camp 2025 is thick with the humidity of expectation. Under the theme “Reclaim Your Future: Secure Your Ecological Future,” a cross-section of Nigeria’s most conscious activists, organizers, and thinkers have gathered. They are the heirs to a decade of explosive, yet fragmented, political awakening. Into this space steps Comrade Baba Aye, a veteran whose voice carries the weight of decades within trade union movements and radical publishing. His lecture title is a question and a diagnosis: “Emerging Role of Youth Revolt and Social Action: Lessons and Gaps.”

The Diagnosis – A Movement at a Crossroads

Baba Aye’s presentation is not a pep talk; it is a clinical dissection of a persistent Nigerian paradox. Nigeria, a nation where over 75% of its estimated 230 million people are under 35, is a demographic volcano. Yet, as Baba Aye argues, this immense energy remains politically orphaned. “Despite decades of activism,” he notes, “Nigeria still lacks a mass party of the working people and suffers from NGO-style fragmentation.”

He paints a picture of movements trapped in a cycle of reaction—mobilizing around a specific outrage (a brutal police unit, a hike in fuel price) but struggling to transition into a sustained, organized political force. Activism becomes “proposal-driven,” donor-defined, a project rather than a project of liberation. This fragmentation, he asserts, is a critical gap. The seismic #EndSARS protests of October 2020 are the ghost in the room. For a few historic weeks, Nigeria’s youth, leveraging technology and raw courage, mounted the most significant challenge to state authority in a generation. An estimated 15-20 million people participated online, with hundreds of thousands on the streets. But the movement, leaderless by design and brutalized by the state-sanctioned massacre at the Lekki Toll Gate, found itself with no political apparatus to convert that mass energy into lasting power.

The anticlimax that followed is a painful reference point. The 2023 general elections, the first major electoral cycle post-#EndSARS, were framed as the moment for the “Obidient” wave and other youth-driven campaigns to translate protest into votes. While voter registration saw a significant surge among youth, the fallout was a lesson in hard politics. The established party machines, built on patronage and ethno-religious fortresses, held firm. The expected tsunami of youth-driven political disruption dissipated into familiar patterns of disillusionment and contested results. Baba Aye’s analysis speaks directly to this: without a “mass party,” revolt risks being an episodic, cathartic scream into the void, not a program for seizing the future.

The Blueprint – Lessons from History and the Bolshevik Analogy

The lecture reveals the core of Baba Aye’s historical-materialist prescription. He confronts the despair of small numbers with a revolutionary realist’s perspective. Referencing his own research, he dismantles the myth of the need for a majority before action.

“We really have not built mass parties… All the membership were just a few thousand, definitely less than 5,000,” he states, referring to historic left parties in Nigeria. Then, he delivers the pivotal analogy: “The Bolshevik party at the time of the revolution… had about 43,000 members in a country with maybe 130 or 140 million people.”

Let that statistic land. In a population comparable to Nigeria’s today, a disciplined organization of 43,000 people changed world history. “But that party,” Baba Aye emphasizes, “carried out a revolution which provided a torchlight… into the darkness of capitalism for several decades.” His point is surgical: it is not about raw numbers, but about the quality of organization, the strategic clarity, and the discipline of that core. The current “NGOization” of struggle, he argues, diffuses this potential, trading revolutionary patience for donor-friendly projects.

Revolution is not about raw numbers, but about the quality of organization, the strategic clarity, and the discipline of that core– Baba Aye

He then weaves this into the global and intergenerational context. The collapse of the Soviet project, he suggests, created a “relative austerity of the imagination” for the current generation—a crisis of belief in systemic alternatives. This, combined with imperialist pressures, fuels the NGO model. The challenge, therefore, is for the “left NGOs” and movements like Social Action to “get more creative in how to take things forward regarding organizing for revolution.”

The Philosophy – The Meaning of Fight, Loss, and Victory

In his final, potent minutes, Baba Aye offers a philosophy for the long haul. It is here his message transcends tactics and becomes moral fuel. He reframes the binary of “win or lose.”

“If we fight, we might win, we might lose. But if we don’t fight at all, we have lost already.” This is the fundamental axiom. But he pushes further: “Winning and betraying are not the only two options… it might be defeat that lays the foundation for subsequent generations to win. So fighting even when we lose is not the same thing as betraying our mission.”

This is a direct salve to the post-#EndSARS, post-2023 election soul of Nigerian youth activism. The Lekki massacre was a defeat. The electoral disappointments felt like defeats. Baba Aye’s lesson is that these are not endpoints, but potential foundations. The awareness raised, the networks forged, the political education hard-won—these are the sediments upon which the next, wiser wave will build. #EndSARS did not achieve a revolution, but it irrevocably shattered the myth of youth apathy and exposed the state’s brutal core for millions. That is a foundational victory.

The Internationalist Vision – Learning from the Global South

Looking forward, Baba Aye, drawing from his experiences with global trade unions, envisions a pan-African and Global South learning ecosystem. He recalls a program that brought together organizers from Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, the Philippines, and Hong Kong. “I learned a lot from them and they learned a lot from each other,” he says. For Nigeria’s often-insular activism, this is a crucial gap. He proposes Social Action could foster similar continental collaborations, creating spaces—like this very camp—where experiences of mass protest, repression, and organizing from Sudan to South Africa, from Senegal to Kenya, are systematically shared.

The Conversation Continues

True to his collectivist ethos, Baba Aye concludes not with a final word, but with an opening: “I look forward to your questions and interventions. It’s always good to have a conversation.” This is the final lesson. The report from the veteran is filed. The diagnosis is clear: a demographic giant, trapped in fragmentation, yearning for a organizational vehicle worthy of its revolutionary potential. The historical precedents are cited. The philosophical armor for enduring defeat is offered. The internationalist path is suggested.

Now, the conversation—and the harder task of building—falls to the generation in the camp, and the millions they represent. The future they seek to reclaim will not be secured by ecology alone, but by a politics as disciplined, as imaginative, and as historically conscious as the challenges they face. The revolt has emerged. The task now, as Baba Aye’s lecture underscores, is to build the institution that can carry it to victory.