Ikarama: Inside the Community Tribunal Challenging Shell, ENI, and the Nigerian State

Ikarama: Inside the Community Tribunal Challenging Shell, ENI, and the Nigerian State

Proceedings of the People’s Tribunal on Environmental Injustice and Human Rights Abuses

On a Friday morning on 21st November 2025, something unusual happened in Ikarama.

It was not a gas explosion, not the sudden glare of a pipeline fire, nor the arrival of security forces to guard oil facilities or disperse protesters. Instead, the community gathered for something far more deliberate and historic: a People’s Tribunal.

For decades, residents of this Bayelsa community have lived as if inside an open ecological graveyard—surrounded by lakes that no longer yield fish, farmlands that ooze crude instead of food, and children who grow up recognising the smell of spilled petroleum more readily than the scent of fertile soil. Yet on this day, Ikarama was no longer just a site of extraction and neglect; it became a courtroom without walls, and the people themselves became witnesses, plaintiffs, and archivists of their own pain.

Men and women, youth and elders who had spent years watching their lands die and their children fall sick walked into a hall not to beg for compensation or listen to corporate promises, but to present their suffering as evidence. This was The People’s Tribunal on Environmental Injustice and Human Rights Violations, a groundbreaking civic intervention convened by Social Action Nigeria and allied organisations.

For the people of Ikarama, this Tribunal was not another “stakeholder meeting” or corporate CSR event. It was a historical reckoning, part of a much longer struggle to secure justice against oil multinationals—particularly Shell and ENI/Agip—and against the Nigerian state, which has failed to protect its citizens.

The Tribunal Begins: Composition, Significance and State Presence

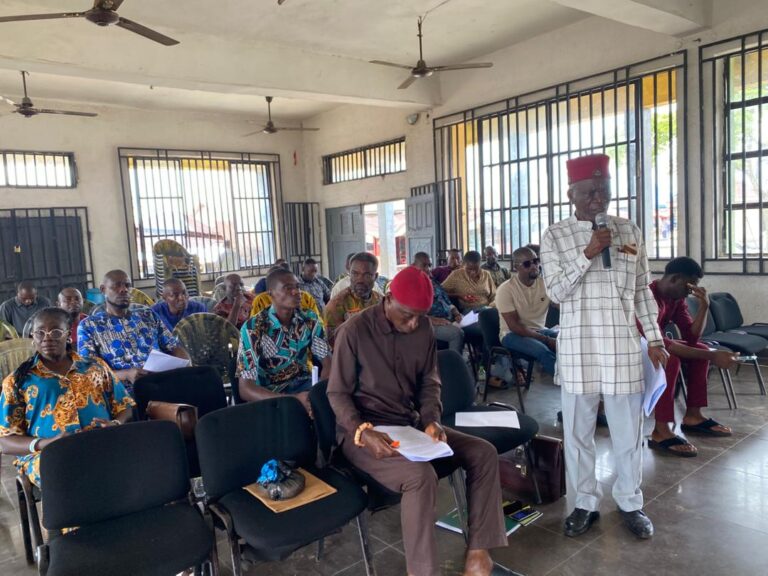

They came from every corner of the community: elders leaning on walking sticks, mothers whose futures had been stolen by cancer and unexplained illnesses, fishermen who no longer recognised the waters they once ruled, young people who have never known Ikarama as anything other than a poisoned landscape.

They gathered in a hall transformed into a public hearing chamber, facing a panel of jurors drawn from legal, medical, gender, and civil society professions. This careful composition signalled that what was about to happen was not a protest, but a structured, quasi-judicial process.

The Jury and Tribunal Officers

The People’s Tribunal commenced with an introduction of the jury members by Peter Mazzi of Social Action. The panel was comprised of esteemed experts:

- Dr. Vivian Brisibe – Vice Chairperson of the Nigerian Bar Association (Bayelsa State) and Chairperson of the Tribunal Jury.

- Dr. Rume Ndokita – Public Health Physician and member of the Nigerian Medical Association, bringing critical insight into the health impacts of pollution.

- Barrister Boma Tonye Miebai – Chairperson of the International Federation of Women Lawyers (FIDA), Bayelsa State, and a prominent gender and human rights advocate.

- Comrade Inatimi Odio – Executive Director of FACE Initiative and member of the Bayelsa NGO Forum (BANGOF), with a long record of civil society engagement and community organising.

Supporting the jury were:

- Miss Priscilla Okpako, Clerk of the Tribunal, responsible for records and administrative coordination;

- Comrade Walson Pamiola, Vice Chairman of BANGOF, serving as Rapporteur, charged with documenting the proceedings and synthesising the Tribunal’s outcomes.

Traditional Authority and Community Leadership

The Tribunal was further dignified by the presence of the traditional leadership of Ikarama, including His Royal Highness, Chief Wariebi Berebozigha, Ama-Miepinamowei the 13th of the Federated Ikarama Communities. His presence situated the Tribunal not only in the language of modern law and rights, but also within the authority of indigenous governance.

Strategic Presence of State Security Agencies

State security agencies were also well represented. The Commissioner of Police, Bayelsa State was represented by the Divisional Police Officer (DPO) of Biseni Division. The hierarchy of the military was present via a representative of the Joint Task Force (JTF), Operation Delta Safe, and the Nigeria Security and Civil Defence Corps (NSCDC) also sent an official delegate. The attendance of the military and security agencies was a deliberate and strategic move that transformed the nature of the event. These institutions, often criticised for protecting oil installations while ignoring or even repressing affected communities, were now seated as witnesses to testimony.

Uniformed officers—members of the police, military, and civil defence—sat quietly in the audience, this time not as enforcers of oil industry security, but as observers of a process designed entirely by ordinary citizens. Their presence silently acknowledged what the Nigerian state had avoided for years: that systemic harm had occurred, and that those harmed had a right to speak.

Opening Remarks: Framing the Case Against Impunity

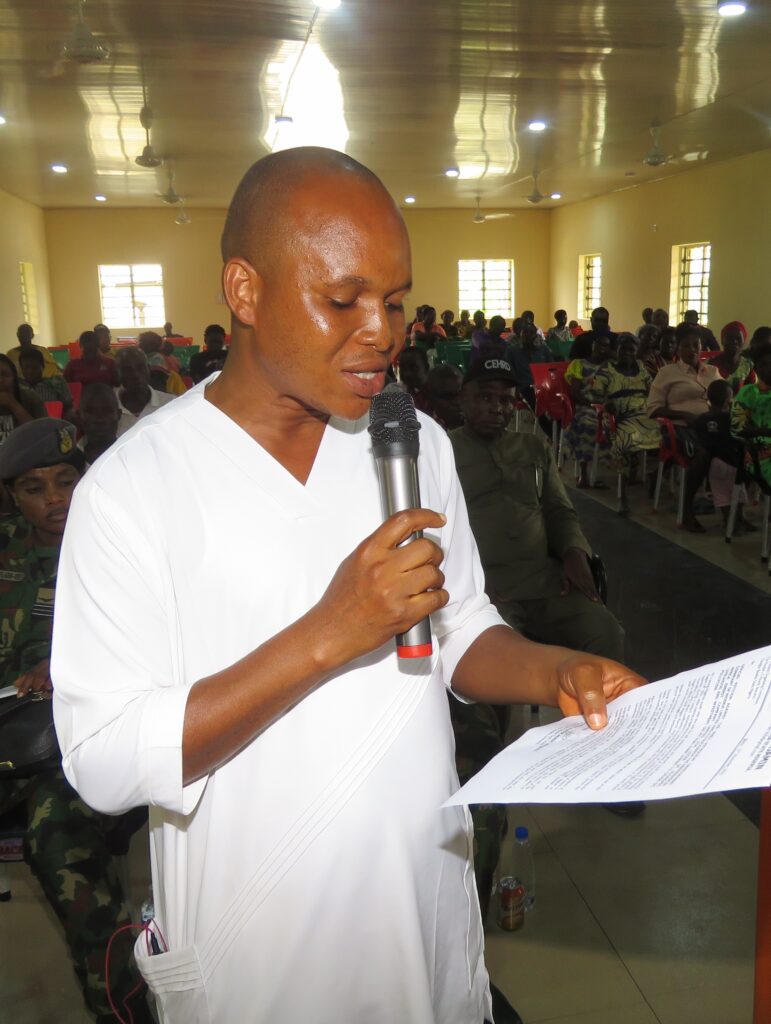

The opening remarks were delivered by Comrade Botti Isaac, Programmes Coordinator of Social Action Nigeria.

He first thanked collaborating organisations and the Ikarama community for their critical partnership in convening the Tribunal. He then moved quickly to the heart of the matter: the profound lack of accountability in Nigeria’s oil and gas industry.

“This Tribunal is a vital, people-centered process. While its verdict is not legally binding, it is designed to give victims, who have been systematically silenced, a platform to be seen, heard, and to articulate their suffering.”

Botti argued that victims of multinational companies—especially in the Niger Delta—have, for decades, been systematically silenced, marginalised, or pacified with tokenistic compensation, despite suffering severe environmental destruction, economic losses, social dislocation, and health crises. He stressed that while the Tribunal’s verdict may not be legally binding in the formal judicial sense, it was nonetheless a critical people’s process, designed:

- to give victims a platform to be seen and heard,

- to document their suffering in a structured and credible way, and

- to transform their experiences into evidence that can inform future legal and policy action.

He highlighted three strategic objectives of the Tribunal:

- Raising public awareness about the specific situation in Ikarama and the broader pattern of environmental injustice in the Niger Delta.

- Informing and supporting future legal processes, including potential litigation and administrative complaints at national and international levels.

- Creating a structured advocacy brief, backed by rigorous documentation, photographs, expert testimony, and first-hand accounts, so that the voices of victims are not lost in the noise of daily politics.

The Tribunal, he emphasised, was not about emotion alone—it was about rigorous evidence and a people’s insistence on justice.

Expert Testimony: A Pattern of Environmental Injustice

The first major testimony came from Comrade Morris Alagoa, a renowned environmental activist and field monitor in the Niger Delta.

Using photographs and field notes, he laid out a compelling case of long-term environmental injustice perpetrated by oil companies—particularly Shell Petroleum Development Company (SPDC) and Agip (ENI)—in and around Ikarama.

He highlighted:

- Recurrent crude oil spills over many years, affecting farmlands, lakes, swamps, and residential areas.

- The widespread practice by contractors of burning spill sites after scooping surface oil, rather than properly remediating the soil and water. This practice, he explained, is not only scientifically unsound but also dangerous, as it drives pollutants deeper into the earth and releases toxic fumes into the air.

- Poorly documented and inadequate clean-up operations, often carried out without meaningful community involvement or independent oversight.

Alagoa’s testimony was not just technical; it was also deeply human. He narrated the tragic case of Mr. Freeborn’s son, a child who died after falling into an unsecured oil spill site following the operator’s slow response. This incident illustrated how negligence at spill sites is not only an environmental issue but also a direct threat to human life.

He also reported an alarming health trend: in recent years, Ikarama has lost at least three women to cancer-related illnesses. In the absence of robust epidemiological studies, these deaths cannot be definitively attributed to oil pollution, but the clustering of cancer and other serious health conditions in heavily polluted communities raises serious public health questions.

Alagoa concluded with a statement that electrified the room: In his extensive years of monitoring oil spills across the Niger Delta, Ikarama has suffered the highest frequency of crude oil spills of any community he has documented.

With that, the Tribunal was left in no doubt: what is happening in Ikarama is not accidental and not isolated. It is part of a systemic pattern of extractive violence.

Presentation of Petitions: Turning Grievances into Evidence

Following the establishment of house rules to ensure order, dignity, and fairness in the proceedings, the Tribunal moved to the core of its mandate: the hearing of petitions.

A total of nine petitions were submitted (eight of which are summarised here), presented by individuals acting in their personal capacity, or as representatives of families, or on behalf of broader community interests. Together, these petitions painted a sobering picture of environmental degradation, economic loss, and human rights abuses.

Petitioner 1: Mr. Nathaniel Osakeme (Akpete Family)

Mr. Osakeme presented a petition regarding the 2018 crude oil spills that affected his family’s lake at Oyoyi land in Ikarama. He described how the spills devastated their traditional livelihoods in fishing and farming. Economic crops and aquatic resources were destroyed. The family’s ability to feed itself and generate income was severely compromised.

He called on the Tribunal to support their demand for adequate compensation for these losses and for proper remediation of the impacted environment.

Petitioner 2: Mr. Daniel Moffi (Akpete Family)

Also representing the Akpete family, Mr. Moffi focused on the health consequences of oil pollution and spill management practices. He reported increasing cases of infertility and low sperm count among men and women of reproductive age, as well as respiratory and visual problems.

He attributed these health problems to prolonged exposure to black carbon (soot) from burnt spill sites and other pollutants associated with oil operations. He called for both compensation and medical intervention, insisting that the health crisis in Ikarama must be recognised as part of the environmental injustice inflicted on the community.

Petitioner 3: Mr. Moses B. (Asawari Family)

Representing the Asawari family, Mr. Moses submitted a petition concerning multiple spills—in 2008, 2018, and 2021—that polluted Oboun Lake. He described the lake as increasingly silted and dying, with blocked water channels, debris, and crude oil residues slowly killing the ecosystem.

He appealed for:

- Environmental compensation;

- Proper and scientifically sound clean-up;

- Eco-restoration of the lake; and

- Economic compensation for the significant loss of livelihoods that depended on the lake’s resources.

Petitioner 4: Chief Evangelist FearGod Francis C. (Landlord of Oya Lake)

Chief Francis, as landlord of Oya Lake, presented a well-documented petition concerning a blow-out at Oya Lake on 23 November 2019, which a Joint Investigation Visit (JIV) report attributed to SPDC.

He explained that the community originally filed a ₦250 million claim for damages. However, due to pressure, negotiation dynamics, and unequal bargaining power, they ultimately settled for ₦10.5 million—an amount that did not reflect the full extent of the environmental and economic damage.

His petition highlighted the problem of coerced or undervalued settlements, where communities are frequently pushed into accepting compensation far below the real cost of damage.

Petitioner 5: Comrade Wada Benjamin

Comrade Benjamin presented a case of economic loss from his private fish farm, which he started in August 2021. During excavation for the ponds, crude oil was discovered oozing from underground—a stark indication of previous spills that had never been properly cleaned.

This finding was later confirmed by NOSDRA, Nigeria’s official spill detection and response agency. The presence of residual oil made the fish farm unviable, effectively destroying his investment and means of livelihood.

His petition underscored how legacy pollution—contamination left behind by past spills—continues to undermine current and future economic initiatives in the community.

Petitioner 6: Engr. Dr. Ibulu Stanley (Aguawari Family vs. Agip)

Engr. Dr. Stanley spoke on behalf of the Aguawari family in a petition against Agip (ENI). He explained that during the 2024 annual floods, crude oil from earlier Agip spill sites became dispersed across a wider area. The floodwaters carried pollutants onto Aguawari lands, Obiowei Lake, and burrowed pits, killing flora and fauna and compounding economic losses.

He informed the Tribunal that he had gathered video and photographic evidence of the pollution. His testimony illustrated how oil spills are not static events but are continually re-mobilised by seasonal flooding, multiplying their impacts over time.

Petitioner 7: Mr. Education (Ozowari Family vs. SPDC)

Representing the Ozowari family, Mr. Education described a long history of environmental impacts from SPDC’s operations. He spoke of:

- Poorly conducted clean-ups;

- Lack of genuine remediation;

- Persistent organic compounds in the water and food chain;

- Loss of economic trees and livelihoods.

His petition emphasised that chronic exposure to pollutants has undermined both health and economic security for his family and the wider community.

Petitioner 8: Mr. Washington Odeyibo (Against SPDC Agent and NSCDC)

Mr. Odeyibo’s petition concerned the 2001 death of his younger brother, who was shot by security personnel over allegations of pipeline vandalisation. The brother, he explained, later died from a tetanus-infected wound, exacerbated by poor medical care.

He noted that the matter was de-escalated by the police at the time, with no criminal charges filed and no serious effort at justice or accountability. His petition highlighted the human cost of the militarisation of oilfields and the failure of institutions to protect citizens even when they are harmed by those meant to provide security.

Why This Tribunal Matters: Context and Broader Significance

To understand the full significance of the Ikarama Tribunal, it is necessary to place it within the wider story of oil, abuse, and resistance in the Niger Delta.

Ikarama as an Archetype of Oil-Related Abuse

Ikarama is not an isolated tragedy. It represents, in concentrated form, what has happened across many Niger Delta communities: oil wealth flows out through pipelines; what remains behind is poverty, illness, polluted water, and ruined livelihoods.

For years, Ikarama’s name has appeared in NGO reports as a red flag—a community with frequent spills, inadequate cleanup, intense corporate presence, and deepening social fractures. The Tribunal shows that Ikarama is not just a “victim community”; it is also a site of organised resistance and strategic documentation.

More than fifteen years ago, Social Action’s report “Fuelling Discord” warned that Ikarama was being reshaped by oil-induced conflict, environmental decline, and the erosion of traditional governance.

ERA/FoEN repeatedly raised alarms about recurring spills and fake clean-ups. Amnesty International and other international NGOs documented the manipulation of spill investigations, the default use of “sabotage” as a defence, and the absence of effective state regulation.

The Ikarama Tribunal builds on this legacy but goes a step further. It demonstrates a new model of resistance: creating a civic courtroom where marginalised communities can produce their own evidence, interrogate power publicly, and build a foundation for future legal action.

The Bayelsa Commission: Scientific Confirmation of Community Realities

The groundbreaking report of the Bayelsa State Oil and Environmental Commission (BSOEC) has been crucial in validating what communities like Ikarama have said for decades. The Commission’s findings—showing widespread environmental contamination, toxic exposure in human bodies, loss of livelihoods, and long-term health risks—provide scientific legitimacy to community testimonies.

The Tribunal in Ikarama thus stands on two pillars:

- Lived experience and testimony, and

- Independent scientific and legal investigations like those of the Bayelsa Commission.

Together, they transform what might once have been dismissed as “complaints” into documented evidence of systemic injustice.

Divestment and Unfinished Business

The Tribunal also takes place at a time when companies like Shell and ENI/Agip have sold off their onshore assets in the Niger Delta to smaller companies. While these divestments are marketed as business decisions, they raise urgent questions for communities:

- Who will clean up decades of pollution?

- Who will pay for the health impacts and economic losses?

- Who will restore contaminated lakes and farmlands?

- How will liabilities be enforced once the original operators have “left”?

The Ikarama Tribunal sends a clear message: oil multinationals can sell infrastructure, but they cannot sell their culpability. Divestment cannot be allowed to function as an escape route from responsibility.

Jury Observations and Recommendations: From Pain to Strategy

At the close of the petitions and expert submissions, the jurors delivered their collective observations and advice, moving the discussion from documentation to strategy.

The jurors strongly advised that the people of Ikarama must move beyond isolated individual claims and fragmented negotiations. They recommended:

- Consolidating petitions and evidence into a unified case or set of coordinated cases;

- Engaging a lawyer specialised in environmental justice and human rights to help shape a coherent legal strategy;

- Using the Tribunal’s proceedings as a formal record to support future action in Nigerian courts, administrative bodies, and possibly international mechanisms.

Building an Evidence-Based Case

The community should establish a solid course of action. The jurors recommended that the community should work with organisations to:

- Commission professional environmental studies, including soil, water, and air quality analysis;

- Undertake a Health Impact Assessment (HIA) to document patterns of disease and reproductive health issues;

- Meticulously itemise economic and non-economic losses (farmlands, fishponds, trees, homes, cultural sites, health costs, etc.);

- Engage a professional valuer to quantify these losses.

They emphasised that while monetary compensation is important, the community should also push for restoration and long-term investments that ensure sustainable livelihoods and rebuild the environment.

Urgency and Legal Time Limits

The jurors underscored the urgency of action, warning that many claims may be constrained by statutes of limitation. This concern was reinforced by the DPO of Biseni, representing the Bayelsa State Commissioner of Police, who stressed the importance of timely eyewitness reports and competent legal representation for effective justice processes.

Appeal from the Traditional Ruler

The Paramount Ruler of Ikarama made a heartfelt plea for sustained support. He noted that some of the environmental and legal challenges facing the community predate his birth, underscoring both the longevity and the inter-generational nature of the crisis. His appeal was a reminder that unless meaningful action follows, the harms catalogued at the Tribunal will continue into yet another generation.