By Isaac Botti, Programme Officer, Social Action, Abuja.

The Nigerian federal government on Tuesday, November 7, 2017, presented its 2018 Appropriation Bill to the National Assembly for consideration and approval. The 2018 federal budget is tagged “Budget of Consolidation”, developed to consolidate on the achievements of the 2017 “Budget of Recovery and Growth”. Taken together, the impression is that the government crafted the earlier budget to revamp and stabilise the economy, while the current proposal is to solidify those gains.

Just how far has the 2017 budget achieved its objectives? How much of recovery and growth has it brought to the Nigerian economy? Has it provided the type of framework where a consolidation is necessary?

How well has the 2017 Budget Performed?

The 2017 budget proposal was based on an economic blueprint that builds on the 2016 budget and was designed to provide a direction of policy actions to achieve economic recovery from the recession and propose a path to steady growth and prosperity. The 2017 budget, was premised on the following critical assumptions;

1. Oil production projection of 2.2mbpd

2. Oil price benchmark of $44.5/pb (this was adjusted from $42.5pb when passing the MTEF)

3. Exchange rate of N305/$1

4. An inflation rate of 15.74

5. GDP growth rate of 2.5%,

These projections were expected to form the operational basis which will catalyse economic recovery from recession.

The 2017 budget was premised on the National Economic Recovery and Growth Strategic Plan that emphasised five broad areas which include macroeconomic stability, competitiveness, growth and diversification, social inclusion and governance and enabler. These five areas were drawn from the reform objectives of the Strategic Implementation Plan of pulling the economy out of recession; investing in the people; and laying the foundation for diversified, inclusive and sustainable growth.

How far have these efforts and blueprints gone in energizing the required reforms?

Capital Spending: At the presentation of the 2017 budget in June 2017, the Minister of Finance confirmed that the government was releasing N350 billion as the first tranche for the implementation of capital projects captured in the budget. This ordinarily would mean that the government is determined to accelerate growth through massive investment in capital projects. Actual release of N336 billion came three months after. This amount represents just 15% of the entire capital budget allocation of N2.2 trillion.

It is important to note that just five ministries gulped 70% of the released sum while the remaining 30% was shared spread across over 300 MDAs. The Ministry of Power, Works and Housing received the largest allocation of N90 billion while Ministry of Defence and Security got N71 billion. Ministry of Transport got N30 billion. Furthermore, Agriculture and Water Resources got N30 billion and N12 billion respectively. All other sectors combined, got a total sum of N103 billion. No further amounts was released for capital expenditure as at the end of the second quarter of the 2017 fiscal year. The government places the blame for this daunting failure on its inability to access foreign loans. This raises a critical concern on the role of external loans in funding the national budget.

Borrowing to Consolidate?

As already stated, the 2017 budget was based on an assumption of an oil production capacity of 2.2 million barrels per day, to be sold at the rate of $44.5 per barrel. How well was this projection achieved? Between May and November, crude oil production in Nigeria has staggered between 1.8 and 2million barrels per day. This reality indicates that the expected revenue will fall short, although the price of crude oil increased significantly from the lowest ebb of $38 in 2016 to $51 as at August and currently at $59. However, in spite of this significant increase in the price of crude oil, projected revenue has not been met. The oil production shortfall is one of the main reasons why the implementation of 2017 budget is complicated, and the government has had to resort to borrowing to augment the gaps. This being the case and with the understanding that only 15% of capital implementation has been achieved so far, it begs the question to ask exactly what the 2018 budget is meant to be consolidating?

Critical Assumptions of the 2018 Budget

In view of the global events and world economic realities, the 2018 budget, like all previous budgets is based on some macro assumptions or guesstimates which are believed to be the best guidelines for driving the 2018 budget implementation. Projection for oil production is pegged at 2.3mbpd; oil price benchmark of $45/pb; Exchange rate of N305/$1; inflation rate of 12.4 and GDP growth rate of 3.5%. The question that should come to mind is ‘how realistic are these projections? Alternatively, are they merely products of ‘guess’ work with no foundational basis for supporting the budget?

Overview of the 2018 Proposed Budget

The 2018 budget proposal has a total figure of N8.6 trillion which represents about 17% increase when compared to the 2017 budget. To achieve this revenue target, the budget proposes a revenue of N6.6 trillion, to be raised from both oil and non-oil sources. It plans to raise N4.165trillion which is 63% from non-oil sources, while N2.442 trillion will be raised from the oil sources.

Revenue Sources

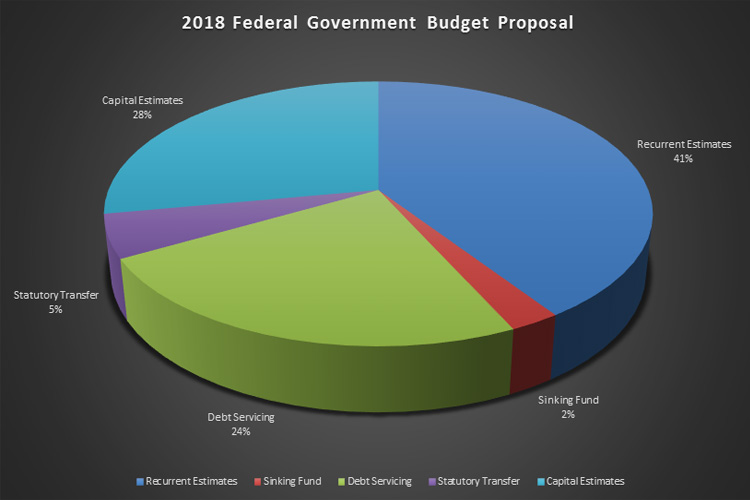

A further breakdown of the budget estimates shows a Recurrent allocation of N3.494 trillion, which represents 40.6% of the entire budget estimates; Just N2.4 trillion or 27.9% of the budget proposal will be spent on capital projects, effectively continuing the dominance of recurrent expenditures. It is important to note that the current capital expenditure proposal is lower than that of 2017 which was N2.98trillion. Equally noteworthy is the fact that allocation for debt servicing stands at an alarming N2.04 trillion.

The 2018 budget proposal has a deficit estimates of N2.005 trillion to be financed through borrowing of N1.6 trillion and revenue from privatised public assets estimated at N300 billion. 50% of the borrowed fund will come from foreign sources while the remaining 50 will be from domestic sources. This implies the government’s borrowing plan is directed at repayment of existing loans rather than investing in development projects. In other words, the borrowing of over N2 trillion is not meant to achieve any economic impact but to be directly sent abroad to creditors, contradicting the provision of the Fiscal Responsibility Act 2007.

Recurrent Expenditure Preference

The 2018 budget proposes N1.5 trillion as recurrent spending in four ministries. The Ministry of Interior gets N510.87 billion, Ministry of Education gets N435.01 billion, Ministry of Defense gets N422.43 billion and the Ministry of Health is to get N209.34 billion. The total amount of the four Ministries represent 43% of the entire recurrent allocations in the budget proposal while the other agencies share the remaining.

Capital Expenditure Preference

On the capital expenditure side, Ministry of Power, Works and Housing, Ministry of Transportation and Ministry of Defense top the list of highest capital allocation of N555.88 billion, N263.10 billion and N145 billion respectively. Other critical sectors such as education, health and trade take the bottom list with N61.73 billion, N71.11 billion and N82.92 billion respectively. Budget lines such as Special Intervention Program also make the top list with N150 billion in capital allocation, while agriculture has N118.9 billion and an opaque Zonal Intervention Projects has N100 billion in capital allocation.

The expenditure plan of the proposal raises concerns about the possibility of the budget leading to any consolidation. For one, it does not seem to take into consideration the pitfall of the 2017 budget, but rather ‘consolidates’ those failures. There is no radical departure from the planning model of the previous year, leading to the conclusion that the result may not be significantly different.