By Omolade Adunbi

Oloibiri is a town located a few kilometers away from the city of Port Harcourt, Rivers State, Nigeria. Locally, Oloibiri is known for sharing the same local government of Ogbia as the town of Otuoke—where Nigeria’s former president, Goodluck Jonathan, was born. Perhaps more noteworthy, however, is the fact that the small Niger Delta town is also widely cited as the birthplace of Nigeria’s oil story. The significance of Oloibiri to the development of Nigeria’s modern economy cannot be overemphasized.

Between 1907 and 1956, colonial Nigeria was engulfed in a frantic search for Black Gold. First, these efforts were led by the Nigerian Bitumen Corporation, a subsidiary of a German company. Soon, the industry was dominated by Shell D’Arcy—a precursor to what is now the Shell Petroleum Development Company of Nigeria.

The Niger Delta embodies the contrived neglect of the majority of Nigerians by a state that continues to fail in its responsibilities towards its own citizens.

It wasn’t until 1956, however, that oil was discovered in commercial quantities in Oloibiri. In 1958, Nigeria made its first shipment of oil to international markets. What began with a production of just 5000 barrels of crude oil a day, was transformed to a two million barrel-a-day oil industry within just two short decades. The growth of the Nigerian oil industry is one on which the country’s economy remains precariously, and detrimentally, dependent.

That oil, and the people of the Niger Delta, have contributed immensely to the development of modern Nigeria is not a contestable question. Yet, if the now used-up and discarded town of Oloibiri proves any example, the Nigerian people are merely resources to be used up and eventually discarded. Oloibiri only lasted from 1958 to 1978 when its oil wells dried up and ended the town’s importance to Nigeria’s ruling elite.

During Oloibiri’s 20-year life span, the town’s oil wells produced approximately 20 million barrels of oil. Today, Oloibiri is a desolate town with nothing to show for the fortune it generated for the Nigerian state.

Today, Oloibiri is a metaphor for what is wrong with Nigeria. As the American anthropologist James Ferguson once noted, there is a usable Africa and an unusable Africa. Usable Africa constitutes those territories with immense natural resource deposits such as oil, limestone, diamonds, gold, coltan, and the like; while unusable Africa constitutes the rest of the continent and its people. The very recent history of Oloibiri suggests that the Nigerian situation is not far removed from Ferguson’s examination.

Once a ‘usable’ part of Nigeria, Oloibiri has today become an unusable space. This has been the sad, but unsurprising, result of economic and environmental plunder by Nigeria’s ruling elite and its multinational collaborators, including Shell, Chevron, ExxonMobil and TotalFinaElf.

During Oloibiri’s 20-year life span, the town’s oil wells produced approximately 20 million barrels of oil that generated millions of dollars for the Nigerian government. Today, Oloibiri is a desolate town with nothing to show for the fortune it generated for the Nigerian state. Water pollution, soil erosion, and an abandoned oil infrastructure, are all that remain from the town’s era of oil production.

In 1958, Nigeria made its first shipment of oil to international markets. What began with a production of 5000 barrels of crude oil a day was transformed to a two million barrel-a-day oil industry within just two short decades.

The poverty levels in Oloibiri today are comparable to the levels found throughout Nigeria as a whole, in which over 50% of the population was living on less than $2 per day in 2012. The people of Oloibiri, however, did not used to be poor. The town’s farming and fishing industries once thrived, leading to a relatively prosperous community of people with a wide variety of occupations and diverse economic opportunities. The unpleasant irony, of course, is that it is the very oil from Oloibiri, which allowed Nigeria’s ruling elite to prosper, that has also led to the degradation of the natural land, and marine, resources of the town, and which once underpinned Oloibiri’s flourishing.

While Oloibiri has since been abandoned by the Nigerian government and its allies among the various international oil companies, ordinary people have had to bear the brunt of environmental degradation, high levels of poverty, impassable roads, and a chronic lack of access to education and quality health services. Life expectancy in the Niger Delta averages just 40 years, compared to between 53 and 55 within Nigeria as a whole.

Top personnel within Niger Delta Development Corporation were recently accused of misusing public funds in what the Nigerian newspaper, Vanguard News, called a “cesspool of corruption.”

In response to the persistent neglect and pillaging of resources throughout the Niger Delta, several militant youth movements have risen up to claim control of the region’s resources; often through violent means. Since 2005, multiple organizations — including the Movement for the Emancipation of Niger Delta (MEND) and the newer Niger Delta Avengers (NDA) — have enacted an insurgency against the state and multinational corporations operating in the region. These groups make various claims about fighting for the rights of the people of the Niger Delta.

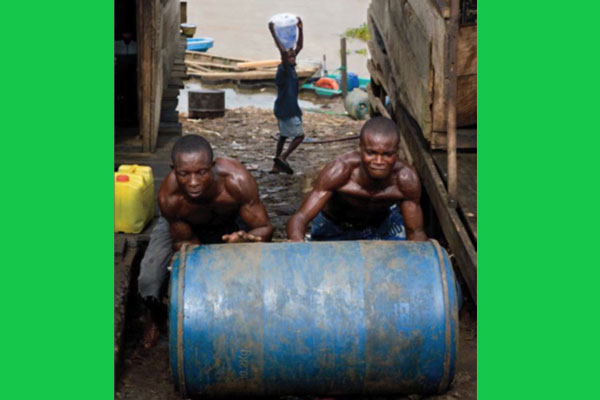

While the Nigerian state and the multinational corporations operating in the Niger Delta have largely dismissed these youths as criminals, they have also continued to ignore the fundamental issues underlying the insurgency. They have refused to address the historical processes that led from a ‘usable’ Niger Delta of the 1950s, to a current population of unemployed, ‘unusable’, youths castigated to the margins of Nigerian society.

Once a ‘usable’ part of Nigeria, Oloibiri has today become an unusable space. This has been the sad, but unsurprising, result of economic and environmental plunder by Nigeria’s ruling elite and its multinational collaborators.

The absence of critical infrastructure such as schools, healthcare facilities, roads, electricity, clean air and water, and the availability of economic opportunities for these youths and their families are rarely at the forefront of official state and oil corporation discussions concerning the Niger Delta. Even when the federal government does dare to focus on such urgent issues of infrastructure development across the Niger Delta, more attention is given to large corporate and government projects than to the actual grievances of local communities.

For example, much attention is given to the Niger Delta Development Corporation (NDDC), a partnership of Shell, Chevron, and other corporations of the Nigerian state that seek to “facilitate the rapid, even, and sustainable development of the Niger Delta.” Unfortunately, such agencies have become a conduit for cronies of the ruling elite to continue the cycles of corruption and exploitation within the region. Top personnel within NDDC, for instance, were recently accused of misusing public funds in what the Nigerian newspaper, Vanguard News, called a “cesspool of corruption.”

Today, when the ‘unusable’ youths see their ‘usable’ environment benefitting others without providing any assistance to their own communities, they resort to violent advocacy. The bleak landscape of Oloibiri epitomizes their worst fears for the Niger Delta. On one hand, the Niger Delta is rendered usable through the extraction of millions of barrels of black gold that account for 80 percent of Nigeria’s government revenue and 40 percent of gross domestic product. On the other hand, the landscape of the Niger Delta is devastated, and the inhabitants must wake up every day in abject poverty to see the oil industry operating all around them, whilst never benefiting their own communities.

Life expectancy in the Niger Delta averages just 40 years, compared to between 53 and 55 within Nigeria as a whole.

The boom and bust of Oloibiri reveals the extent to which the Nigerian government views most Nigerians as nothing more than one out of many useable resources to be exploited, and then discarded. The Niger Delta embodies the contrived neglect of the majority of Nigerians by a state that continues to fail in its responsibilities towards its own citizens.

This is a failure of responsibility that is apparent towards the people and communities of the Niger Delta in particular, and towards all Nigerians in general. It is a failure of responsibility that has reduced the bulk of the Nigerian citizenry to a disposable commodity of usable and unusable objects.

Omolade Adunbi is a member of the Governing Board of Social Action. He is a political anthropologist and Associate Professor at the Department of Afroamerican and African Studies (DAAS) at the University of Michigan. He obtained his PhD in Anthropology from Yale University and a Bachelors’ from Ondo State University, Ado-Ekiti, Nigeria. His latest book, ‘Oil Wealth and Insurgency in Nigeria’ addresses issues related to oil wealth, multinational corporations, transnational institutions, NGOs and violence in the oil-rich Niger Delta. This piece was first published by politicalmatter.org